In an earlier post I gave tips on how to write a logline but even people who’ve read that article have been sending me loglines that aren’t as strong as they should be. So here is a companion piece to help sharpen your understanding of one of the screenwriter’s most powerful tools.

I love the logline. Specifically, I love the logline that’s just a single sentence of no more than 27 words. I love it because it helps you identify the dramatic conflict at the core of your story and it helps you test whether your concept is sufficiently simple and compelling to attract a cinematic audience. But there are good loglines and there are ordinary loglines. Here are the 6 most common mistakes I see – and how to avoid them.

Most common logline weakness #6: Too complex

Take a look at this logline I pulled from this week’s TV guide for the Keira Knightley flop, Domino:

While being profiled by a reality TV crew, a teenage-model-turned-bounty hunter and her companions get in over their heads tracking down those responsible for an armoured car robbery.

That’s a single sentence and remarkably it’s only 28 words. But is it simple? Reality TV crew? Model turned bounty hunter? Armoured car robbery? Of course, if you’d questioned the writer, they would have said, “But this really happened!”, because it did. But if I’d been pitched this, I would have responded with the immortal words of Sydney Pollack in Tootsie, “Who gives a shit?”. It’s too complex and, what’s more, none of the elements complement one another.

By contrast, take a look at Inception. The plot of this Christopher Nolan blockbuster is, depending on your point of view, either breathtakingly or mind-numbingly complex, but the concept is simple. Here’s my take on the logline for Inception:

To regain his estranged children, a guilt-ridden dream thief risks his life to overcome heavily armed cerebral defences and plant an idea in a business mogul’s mind.

Plant an idea in someone’s mind? If you haven’t seen the film, you’ll have no idea how he might do that but it’s an intriguing quest, yes?

Your plots can be complex but your logline must clearly and simply express the big idea that’s central to your story.

Most common logline weakness #5: No external quest

A lot of loglines I see describe the character’s inner journey but contain no external quest. Here’s an example I’ve made up to illustrate the point:

A political crisis forces a cynical, womanising US President to choose between career and family.

There’s a transformation here. He’s going to move from being focussed on his ambition to caring about his wife and children. Great. But what’s the quest? A political crisis? Not specific enough. What does the guy have to DO that’s going to trigger this epiphany? This logline is all inner journey and not enough outer conflict.

Don’t get me wrong. I love the inner journey. I love it because it’s the inner journey, the transformation of the protagonist, that ultimately moves us – not the getting of the McGuffin.

But audiences generally don’t decide to go see a film because of the inner journey.

“Hey, Joe. We gotta go see The Hangover.”

“Why? What’s it about?”

“It’s about a bunch of guys whose lives are changed by a weekend in Vegas. Totally freakin’ transformed. You with me?”

“… No, I think I’m gonna go shoot me an elk. With my man friends.”

Yes, The Hangover does transform its characters and it’s a very important part of why the movie works but that’s not why people went to see it. Why did they go see it?

After a wild Vegas Buck’s Party, a dysfunctional bunch of guys wakes with no memory of last night, a tiger in the bathroom – and no groom.

Audiences flocked to see a bunch of hung-over guys try to find Doug – and maybe to find out who was the rightful owner of that feline. They didn’t go for the inner journey. They went for the external journey.

In the logline, the inner journey is generally much less important. I like to see the hint of it. Which is why I suggest that you include the hero’s flaw. But if your logline doesn’t indicate a strong and enticing external quest for the hero, and you’re relying largely on the internal journey, you’re probably in trouble. Why? Because in many ways the inner journey is always the same.

The inner journey typically moves the hero from striving for achievement to seeking fulfilment. From thinking about the self to thinking about others. More generally, I would say that the inner journey is about transforming the hero from a child into an adult – which is why in many ways every good film is a coming-of-age story.

That’s why my illustrative logline is so unconvincing. No-one is going to go to the movies to see a politician choosing family over career. They can see that on the evening news. I expect your screenplay to contain an inner journey, but unless you can tell me something about that crisis that makes me sit up and take notice, I too might go and shoot me an elk rather than go to this particular movie.

Most common logline weakness #4: Not enough conflict

Let’s take that last logline and get more specific about the crisis:

As he strives for a second term, a cynical womanising US president must choose between his career and his family.

OK, so the quest is now more specific. He’s trying to be re-elected. Great. But why is that going to be difficult? True, his womanising is a potential obstacle in a Presidential race – just ask John Edwards – but as the incumbent, he’s got a huge advantage over any challenger. Why is this going to be so hard?

This is a very typical weakness in loglines. There’s an external journey but it’s not clear to me why it’s going to be difficult for the hero to achieve their goal. And, that’s not going to work. Because drama is conflict.

Life is tough – we know that from our own struggles. So we’re not going to shell out our hard-earned to go see someone do something that is less challenging than what we do on a daily basis.

Look at the quest described in your logline? Does it sound difficult enough? Does the goal seem impossible to attain? Are the forces of antagonism sufficiently intimidating? If not, beef up that conflict either by diminishing the capacities of the protagonist or increasing the power of the antagonist.

Most common logline weakness #3: Not original enough

Let’s take that last logline and beef up the conflict:

When aliens invade Earth, a cynical womanising US president must choose between his career and his family.

OK, so the quest is now more difficult because those aliens, typically, are tough little varmints. But why won’t we flock to see it? Because there’s no novelty factor.

Since, as I’ve pointed out, there’s not a lot of variation in the inner journey, what audiences are looking for is a fresh skin on that hero’s transformation. They want to see someone do something they haven’t seen done before.

The inner journey of Dead Poets Society is exactly the same as The King’s Speech. It’s about a character finding the courage they need to give voice to their essence. Both Todd (Ethan Hawke) and King George VI (Colin Firth) are metaphorically mute at the beginning but overcome their fears to gain self-respect and inspire others. But we go to see The King’s Speech because it has a fresh take on this timeless transformation.

As he prepares to tell Britain it’s at war with Germany, King George VI engages an impertinent Australian speech therapist to try to overcome a crippling stammer.

The inner journey is implicit. The stammer is just the most obvious manifestation of his lack of self-belief. So the logline can focus on the specifics of its totally original external quest. It’s made all the more intriguing because it’s true. This is a GREAT concept.

Take a look at your logline. Is it like anything else that’s already been made? You might say that your feature animation concept about a bunch of gentrified zoo animals that gets stranded on the Maldives is TOTALLY different to the film about the gentrified zoo animals that get stranded on Madagascar. But will Hollywood’s script readers read past the logline to discern the nuanced distinctions?

If it’s not original, try to tweak your idea so that it is or ditch it.

Most common logline weakness #2: Stakes not high enough

To illustrate this point, I’m going to look at two different loglines for the film, Easy A.

Firstly, here is the official logline pulled from IMDb:

A clean-cut high school student relies on the school’s rumour mill to advance her social and financial standing.

OK, now I would say there were stakes here. At high school, what could be more important than your social standing. They are massive stakes and it’s what drives Tina Fey’s film, Mean Girls. However, that’s not an accurate description of the Easy A you’ll see on the screen.

Here is my logline for the Easy A I saw:

After she pretends to sleep with a gay friend to enhance his social standing, a confident, attractive, sharp-witted teenage girl is overwhelmed by nerds seeking to lift their daggy profiles.

Her gay friend wants to raise his social standing. He’s got stakes. The nerds want to raise their social standing. They’ve got stakes. But what’s in it for Olive? Emma Stone is fabulous in this role but the film dies in Act 2 because Olive has no compelling reason to do any of this. There are no stakes. And if there are no stakes, why should we care?

Why must your protagonist undertake their quest? What is their motivation? We don’t have to agree with their motivation – they could be doing it for wholly selfish reasons. But we need to sense the stakes or we’ll question whether the film will have sufficient narrative drive to maintain our interest.

Most common logline weakness #1: No anticipation

Sometimes your logline can tick all the boxes:

- Engaging protagonist

- Clear external quest

- Strong forces of antagonism

- Flaw hinting at hero’s transformation

- Original idea

But it still might not mean you’re sitting on a massive cinematic property. Why? Because your logline might not get our juices flowing.

A great logline, in just 27 magical words, conjures the film in our heads. We can see it. We imagine the dramatic or comedic possibilities and we go, oh, yeah, I’ve never seen that before. I’ve GOT to go see that.

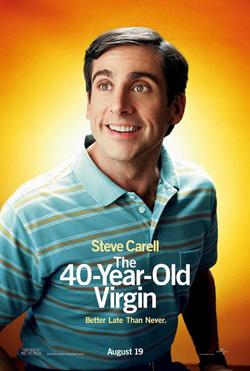

Think about 40 Year Old Virgin. Hell, they’ve got me with the title. Already I have two questions I want answered:

1. Why is he still a virgin?

2. How is finally going to get laid?

The logline might have read something like this:

After his wham-bam workmates learn he’s never had sex, a shy nerd has to suffer their crude tutelage as the girl of his dreams sails away.

We’re going to see his buddies try to teach him how to get on with “the ladies”– that’s where the comedy’s going to be. The “Fun and Games”, as Blake Snyder puts it. That’s what we’re anticipating. But we also know that ultimately he’s going to have to find the courage to ignore their “advice” and win his one true love. High concept married to inner journey. Winner.

But you don’t have to be at the blockbuster end of the concept spectrum to create a sense of anticipation. Here’s the logline for Brokeback Mountain.

When a taciturn cowboy falls for a fellow married cowboy in 60s Midwest America, he’ll have to come out or risk losing the love of his life.

Brokeback wouldn’t be considered a high concept film. But when you read that logline you can see the film. Gay cowboy? In the 60s? In the American west? You can feel the dramatic tension. You can sense the silences heavy with unexpressed emotion. And, with a title like Brokeback Mountain, you can picture the spectacular backdrop. It’s a great idea because it makes you ache with anticipation.

Of course, sometimes a concept creates a sense of anticipation that the film doesn’t fully deliver on – I’d put Yes Man in this category – but that’s not the fault of the idea. That’s down to execution.

Does your logline create a sense of anticipation? When you tell people your idea, do they get a smile on their face even before you’ve finished pitching it? That’s always a good sign. If they go, “That’s … interesting”, chances are it isn’t.

Of course, it’s true, you don’t need to have a big idea to create a successful film. Pulp Fiction wouldn’t have read well in a logline – multi-strand narratives rarely do – but it was huge. Star Wars, at a concept level, was unremarkable, but it did reasonably well too I believe. And take a look at this logline:

After being dumped by his girlfriend, an abrasive nerd creates a massive website that triggers 2 lawsuits – including one by his one true friend in the world.

Would you have gone to see The Social Network based on the logline? No, probably not.

So concept isn’t everything and the logline isn’t an infallible indicator of a movie’s merit. But you’re competing with hundreds of thousands of other screenwriters who are trying to get their films into production. And that’s before you get to fight the real battle of putting bums on cinema seats. I can assure you that if you’re able to not only communicate your concept but create a genuine sense of anticipation in a single sentence of just 27 words, you are WAY ahead of the pack.

If your logline either isn’t sufficiently dramatic or it doesn’t have that wow factor, you’re left with a difficult call. Do you persist, confident that you can still write a great screenplay despite an uninspiring logline, or do you set the idea aside and try to find a concept that is unarguably compelling?

That’s a call only you can make. But I hope this post has helped ensure that you write a logline that realises the full potential of your idea and gives your screenplay the best possible chance of going into production.

Join the Cracking Yarns mailing list

Learn about our Screenwriting Courses

Learn about our Online Screenwriting Courses

Learn about our Free Screenwriting Webinars

Learn about our Script Assessment options

Subscribe to the Cracking Yarns YouTube channel

Related articles:

How to write a logline

How to write better loglines

Why the Social Network shouldn’t work (and why it does)

Why Inception didn’t do it for me

Easy A gets A+ for character but C- for story