The Hero’s Journey transformed my storytelling but there is one area where I diverge from Chris Vogler’s thinking – and that’s on Character Arc.

Back in ’93 when I was living in LA, I was at a very low point in my life. For a start, I was living in LA. But then someone gave me a book that totally altered my understanding of story. That book was Chris Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey.

Why the Hero’s Journey does it for me

I like the Hero’s Journey because it wasn’t invented by some Hollywood hack – rather it’s a story pattern that was identified by mythological guru, Joseph Campbell, after gathering and exploring the great enduring stories from all cultures across all time.

I like the Hero’s Journey because it wasn’t invented by some Hollywood hack – rather it’s a story pattern that was identified by mythological guru, Joseph Campbell, after gathering and exploring the great enduring stories from all cultures across all time.

I like the Hero’s Journey because – if your Muse is with you – it can help you deliver the kind of emotionally powerful films that I want to write and audiences want to see.

And I like the Hero’s Journey because it’s incredibly flexible. In my screenwriting courses, I cite hundreds of examples of great films that – consciously or unconsciously – use the Hero’s Journey structure: from Dead Poets Society to Groundhog Day; from Schindler’s List to Brokeback Mountain; from Little Miss Sunshine to The King’s Speech.

But there’s one thing Vogler says that I simply can’t agree with. And that’s his take on the Character Arc (page 205 in the Third Edition).

What Vogler says about Character Arc

Here’s Vogler’s Character Arc mapped to the 12 stages of the Hero’s Journey:

- Ordinary World – Limited awareness of problem

- Call to Adventure – Increased awareness

- Refusal of the Call – Reluctance to change

- Meeting with the Mentor – Overcoming reluctance

- Crossing the first threshold – Committing to change

- Tests, Allies & Enemies – Experimenting with first change

- The Approach – Preparing for big change

- The Ordeal – Attempting big change

- Reward – Consequences of the attempt

- Road Back – Rededication to change

- Resurrection- Final attempt at big change

- Return with the Elixir – Final mastery of the problem

In short, Vogler says that your protagonist should evolve gradually in incremental steps from the start of the film to the end. He rationalises it this way:

A common flaw in stories is that writers make heroes grow or change, but do so abruptly in a single leap because of a single incident. Someone criticises them or they realise a flaw, and they immediately correct it; or they have an overnight conversion because of one shock and are totally changed at one stroke. This does happen once in a while in life, but more commonly people change by degrees, growing in gradual stages from bigotry to tolerance, from cowardice to courage, from hate to love.

Chris, I owe you so much and I can’t thank you enough, but I’m afraid I categorically and passionately disagree with you here.

Why I disagree with Vogler on character arc

It’s Phil Connors’ flaws that make him funny and he’ll make no attempt to address them until Rita (Andie MacDowell) gives him a good slapping at the Ordeal.

In the films that I love most dearly, protagonists do not change gradually by degree. In fact, they’ll do anything they can to avoid making any change until they have no choice – until they are confronted with that flaw, generally by the antagonist, at the Ordeal (or midpoint in Classical theory).

Take Todd (Ethan Hawke) in Dead Poets Society. He cowers in the shadow of his high achieving brother – and hides behind the apron of his room-mate Neil (Robert Sean Leonard) until Mr Keating (Robin Williams) confronts him with “his greatest fear” around the middle of the second act in the famous “sweaty tooth madman” scene. There’s no gradual change. He’s transformed – and credibly transformed – in that one scene.

Take Phil Connors (Bill Murray) in Groundhog Day. Trapped in Punxsutawney on Feb 2, he uses his special knowledge to steal from armoured cars and bed the local talent like Nancy from Mrs Walsh’s English class. He is making no attempt at change, indeed he is looking to add another notch to his bedpost – shame it will be gone in the morning – when Rita (Andie McDowell) confronts him with his flaw. Slap! “I could never love someone like you because you’ll never love anyone but yourself.” Slap, slap, slap, slap, slap. Before it, he’s hugely flawed. After that scene, he’s a changed man.

Take Zack Mayo in An Officer and a Gentleman. He’s looking after number one until his mentor/antagonist, Foley (Lou Gossett Jr) tells him that “This isn’t about flying jets. This is about character”. Zack enters the scene as a selfish loner and emerges realising that if he’s to make it through the program – and succeed at life – he’s going to need to move from being focussed on the self to thinking about others. The change happens in one scene.

Why your character’s change shouldn’t be gradual

There are 2 reasons why I would discourage you from having your characters change gradually as Vogler recommends:

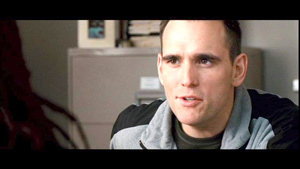

Matt Dillon’s Officer Ryan is a racist bigot in Crash – but it’s precisely this flaw – and the contradiction that he’s a loving son – that make him interesting. Don’t make the mistake of having your characters address their flaw too early.

Firstly, characters tend to be most interesting when they are most flawed. Miles (Paul Giamatti) in Sideways. Rick (Humphrey Bogart) in Casablanca. Officer John Ryan (Matt Dillon) in Crash. If these guys start losing their edge early in Act 2, they start getting boring. This is particularly important in comedies where you’re laughing precisely because the hero is flawed. Phil Connors at the start of Groundhog Day is hilarious because he is so egotistical, so arrogant, and the writers thankfully keep him flawed as long as they can – because once he’s transformed he’s almost sickly sweet.

The second reason I don’t think that your characters should address their flaw too early is that it diminishes the conflict and the emotional power of that confrontation scene I’ve described above and which I explore at length in my post on the midpoint/ordeal.

If the character is already aware that he has a problem and has made some effort to change, the antagonist doesn’t have as much at which to aim and the protagonist has much less distance to travel. The emotion we feel when we watch these pivotal scenes comes from seeing someone being dragged kicking and screaming out of their flawed state and into enlightenment. Why does it affect us? Because, as humans, we know how difficult it is to change.

You might say that this massive and sudden change is not representative of life. I would say that it’s not unrepresentative of life. Very often, it’s only a massive confrontation that will change people’s behaviour. A heart attack convinces someone to eat healthily, take up walking and give up the ciggies. A jail term convinces a junkie to give up the gear. The loss of a career, wife and family convinces a guy to give up the duplicitousness.

I would also say that, in the end, I’m not trying to replicate life on the screen. I’m trying to tell a story that resonates for the audience, and delivers the emotional power for which they shelled out their hard-earned. Incremental change doesn’t produce that; sudden and radical transformation does.

That doesn’t mean the hero should keep hitting the same beat

Although I don’t believe the protagonist should address their flaw until they have this confrontation at the Ordeal, that doesn’t mean that your hero should be making the same mistake, over and over again, until the Ordeal.

In Groundhog Day, even though Phil Connors won’t address his flaw until Rita (Andie MacDowell) has slapped him half a dozen times, he doesn’t keep doing the same thing. In the 1st sequence of the 2nd act, he makes new friends in the bar and tests his powers by playing chicken with a train. In the 2nd sequence of the 2nd act, he conquers (and proposes to) Nancy, safe in the knowledge she won’t hold him to it in the morning. In the 3rd sequence, he goes for the grand prize – Rita – and meets his match.

Nothing infuriates me more than characters who do the same things over and over again, which explains why Easy Virtue was such a frustrating experience. Larita (Jessica Biel) and Mrs Whitaker (Kristin Scott Thomas) have the same fractious conversation, again and again and again.

And just because I don’t think the hero should begin addressing their flaw before the Ordeal, that doesn’t mean that you can’t reveal some redeeming qualities in the interim. For example, Officer Ryan in Crash is shown to be not just a horrendous racist but also a loving son. Miles in Sideways, when he talks about Pinot Noir and unconsciously describes himself, also gives us a glimpse of the sensitive, loving man trapped within that frustrated author. And after his father, King George V, dies Bertie (Colin Firth) in The King’s Speech opens up to Logue (Geoffrey Rush) and finds his first real friend. But in each of these films, despite these scenes which reveal a softer side to the hero, the flaw goes unaddressed – which means the potential for drama at the Ordeal remains undiminished.

In the films that I love, the protagonist doesn’t begin to address their flaw until after the Ordeal, but, before we reach that point, the writers find fresh ways to dramatise the hero’s flaw or to reveal warmer dimensions that are a counterpoint to the character’s more obvious failings.

That I am a huge advocate of having the hero constantly shift emotional gears will be abundantly apparent when I outline my 12-step Hero’s Inner Journey.

A new character arc for the Hero’s Journey

I have developed a very different 12-step character arc that focuses more on the Hero’s Emotional Journey and which guides my writing far more than the well-known 12 steps of the Hero’s Outer Journey. It’s a new, more character-driven Hero’s Journey.

Click here to discover the 12 steps of my new Hero’s Emotional Journey.

I’d like to join the Cracking Yarns mailing list

When is my next 2-day screenwriting course?

Related screenwriting articles

A new character-driven Hero’s Journey

What should happen at the midpoint

10 screenwriting insights I wish I’d had 25 years ago

Why I love the Hero’s Journey

Hero’s Journey breakdown of The King’s Speech