The ending of Juno the script isn’t the same as Juno the film. It’s much more powerful – and it holds a valuable dramatic lesson for screenwriters.

I was reading the screenplay of Juno this week and when I reached the climax I burst into tears. That doesn’t happen all that often. I’m constantly moved by clips I show in my screenwriting courses, but I can’t think of too many scripts that made me sob (for the right reasons at least). So I was looking forward to re-watching the film. I was to be hugely disappointed.

The ending of Juno as directed by Jason Reitman is different to the screenplay as written by Diablo Cody – and doesn’t pack anything like the same emotional punch. Let’s take a look at how they differ, why the screenplay is more moving, and what we can take away as screenwriters.

The climax of Juno – in the screenplay

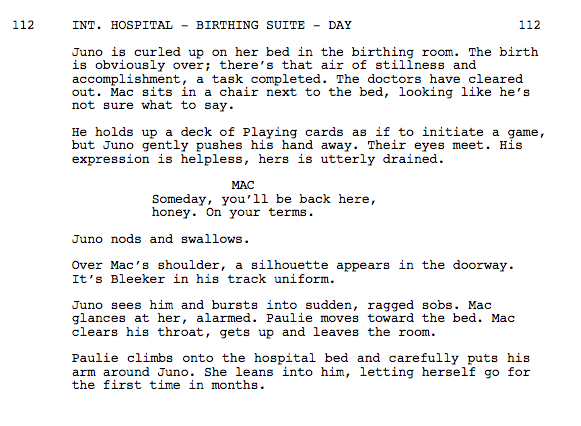

In the published Juno screenplay, here’s what happens at the climax:

4. A nurse asks “Would you like to meet your son?”, but it’s not Bleeker she’s talking to but the adoptive mother, Vanessa.

6. And now the clincher scene of the climax – as written. Mac is Juno’s father (J.K.Simmons).

The Climax of Juno – in the Film

Now let’s look at the ending chosen by the director, Jason Reitman.

Why is Juno’s screenplay more moving than the film?

Were you moved by the climax of Juno? I wasn’t. I loved the film. I still love the film. But I wasn’t affected by the finale. Not when I when I saw it in the cinema. Not when I re-watched it. Why did the screenplay move me but the film didn’t?

It comes down to the fundamentals of drama:

- Set up the dramatic question in Act 1

- Build the tension to unbearable levels in Act 2

- Answer the question – and release the tension at the climax of Act 3

The screenwriter Diablo Cody does this perfectly. She sets up the dramatic question at the end of Act 1: Will Juno adopt out this child, or will her relationship with Bleeker cause her to change her mind?

Through Act 2, the screenwriter swings the pendulum back and forth, giving us reasons to think she might keep the child and reasons to think that she might hold on to her original plan.

Then with the breaking of Juno’s waters, we know decision time is coming: a classic dramatic crisis or Act 2 Turning Point.

By showing the baby being handed not to Bleeker, as we’re expecting from the lead-in scene, but to the adoptive mother, Vanessa, our dramatic question is answered. Juno is adopting out the child.

Yet this doesn’t dissipate the dramatic tension. It only serves to increase it because we haven’t yet seen the decision’s emotional impact on the two characters about whom we care the most: Juno and Bleeker.

Cody then builds that tension a little more in the poignant moment between Juno and her darling father, Mac, when he says she’ll be back here on her own terms.

We’re now aching for the resolution. So when you read in the screenplay that “a silhouette appears in the doorway”, the hairs go up on the back of our necks. Juno looks at Bleeker and – Whoosh!

Nothing more needs to be said. Nothing more needs to be done. In this single cinematic moment, we feel the pain of Juno’s incredibly difficult choice, the anguish of the last 9 turbulent months, and the shared sense of loss – however “right” the decision might be for a couple of schoolkids. Like Juno, we burst into “sudden ragged sobs”. Brilliant climax.

Why Reitman’s version isn’t as as effective

Unfortunately, the director didn’t render on the screen what the writer put on the page. I don’t know whether he consulted the screenwriter on the changes but it’s telling, I think, that the published screenplay doesn’t match the film. When Cody was up for Best Original Screenplay, she clearly wanted them considering her version. Smart move; she won the Oscar – and deservedly so.

What’s amazing is that Reitman doesn’t greatly change what’s in the scenes. The diminished emotion we feel is mainly the result of changing the order of the scenes.

The crisis is set up in the same way – Juno’s waters break and Bleeker isn’t there.

But then the director leaves out the crucial step of building the tension – the scene where Vanessa gets the child, and we learn that Juno is giving it up, doesn’t happen here.

Instead, in the film, we cut straight to the scene where Mac is consoling Juno. So our dramatic question has been answered and Juno is in the room so already some precious dramatic tension has been dissipated.

That would be bad enough, but then the tension is further undercut by Juno’s wisecrack about Bleeker’s “nice legs”. Juno’s flaw at the start of the film is that she’s too cool for school – too concerned with maintaining her insouciance rather than being honest with Bleeker about her doubts and emotions. In this moment, we need to see that façade – that “identity” – stripped away by raw human emotion. The writer does this in her screenplay. Unfortunately, in the director’s version, it’s the same old smartass Juno, which means that as a character she’s gone nowhere.

Then the director gives us the scene that the writer wanted to appear earlier – where Vanessa gets the child. But in this location, its dramatic effect has been lost.

Perhaps aware that the climax hasn’t quite worked, the director takes us back for another shot of Juno sobbing in bed but by then it’s too late. The moment has been lost and there’s no resurrecting it.

Why Reitman might have changed the ending

In discussing this with my AFTRS colleagues, someone suggested that Reitman might have been trying to diminish any animosity we might feel for the adoptive mother and that politically this might have been important.

I can see this might have motivated Reitman to make a change. But I didn’t have a problem with the treatment of Vanessa in the screenplay – Bren’s presence softens it wonderfully – and to me it’s putting the cart before the horse. Our priority needs to be our protagonist.

It’s quite possible that Reitman doesn’t like emotionally powerful endings and consciously sought to underplay it. Given that the climax of another of his films, Up in the Air, failed to pack any punch, this is quite plausible.

However, I believe our primary mission as filmmakers is to deliver an emotionally powerful ending to the punters in the seats, and, as filmed, Juno doesn’t do that for me.

What Juno teaches us about creating powerful endings

If I ask a screenwriter to describe the moving climax of their film and they say, “This happens, and then this happens and then this happens and then this happens and then … “, I know they’re in trouble because I can see that their climax is about concluding plots rather than generating emotion.

If you want your film to deliver a powerful ending, you can’t get your audience to think their way through the climax. They need to feel it. And in this regard it might be helpful to think of yourself as an archer with a bow and arrow.

Why screenwriting is like archery

In a beautifully constructed climax like the one in Juno the screenplay, the screenwriter draws the arrow back, and then she draws it back a little further, and then she pulls it back until the string is at breaking point, before releasing it and – THWACK – the arrow hits us right in the heart.

In a beautifully constructed climax like the one in Juno the screenplay, the screenwriter draws the arrow back, and then she draws it back a little further, and then she pulls it back until the string is at breaking point, before releasing it and – THWACK – the arrow hits us right in the heart.

In a fragmented climax, like the one in Juno the film, the arrow is drawn back and it all looks great, but then instead of drawing the string back further, the tension is released a little, then it’s released a little further, and by the time the arrow is finally sent towards its target, it just goes PLOP, and falls on the ground in front of us.

Movies are about moments.

Getting your audience to connect with your character happens in a moment – like Erin Brockovich (Julia Roberts) saying to the lawyer (Albert Finney) she desperately wants to work for, “Don’t make me beg”.

And getting us to connect more deeply with our protagonists happens in a moment, like Ennis (Heath Ledger) breaking down when Jack (Jake Gyllenhall) threatens to end their relationship in Brokeback Mountain.

And, most importantly, getting us to feel great emotion at the climax needs to happen in a moment. You don’t get 4 or 5 scenes to deliver that emotional punch. Or even possibly 4 or 5 shots. All the tension you’ve artfully developed over the preceding hour and half, and especially in the final 10-15 minutes, needs to be released in a transcendent moment. Diablo Cody created it. Unfortunately, to experience her full genius, we need to read her screenplay rather than see the finished film.

With your screenplays, I hope when you release your arrow it goes THWACK rather than PLOP. And that if you manage to make that remarkable thing happen, that you and your audience get to see it faithfully rendered up there on the screen.

Here’s my Hero’s Emotional Journey breakdown of Juno – as written, not as directed.

Join the Cracking Yarns mailing list

When is my next 2-day screenwriting course?

Related screenwriting articles:

Why can’t people write good endings any more?

Where I disagree with the Hero’s Journey

A new character-driven Hero’s Journey

Why the ending of The Town doesn’t work

10 screenwriting insights I wish I’d had 25 years ago