I wandered in the wilderness for a long time as a writer because almost all of the screenwriting bibles fail to address the most fundamental question: Why do we need stories?

When it comes to endings, you can tick all the boxes in terms of theory but ultimately there is only one thing that matters.

A profoundly moving ending depends first on building tension. But how you release that tension is just as critical.

While your audience will generally want your hero to gain something, for a truly great ending you’ll also have to make sure your protagonist loses something very dear.

If you want to end your film on an affecting up beat, you’re going to need to precede that with a very significant down beat. (Or vice versa).

An emotionally powerful ending depends on 2 key moments before the climax itself. And neither of them is the Inciting Incident or a Turning Point.

Most screenplays have some sort of character arc but this “transformation” typically fails to move us. Here I explore what sort of change does tend to profoundly affect your audience.

In the great endings the hero typically does in the final act what they could not have done at the beginning, and this shift seems to be fundamental if you want to profoundly move your audience.

Most screenplays suffer because the resolution comes too easily. You must make it really hard for your hero – and that doesn’t mean making the antagonist 6 inches taller or 40 IQ points smarter.

In the last post, I noted the hero rarely gets what they wanted in a profoundly moving ending. Here we explore the ecstasy they get to balance the agony.

Think your hero needs to triumph at the climax to satisfy the audience? That’s a rookie mistake. Here’s why …

The films we love tend to have profoundly moving climaxes. In my next 10 posts I’ll explore how to craft a truly transcendent ending.

My final tips to the departing AFTRS Grad Cert Screenwriting cohort of 2013.

If you want to write a Transcendent Story, don’t think happy or sad ending. Think “Ecstatic Agony”. Here I explore what that means and why it’s so powerful.

Here I identify five characteristics of the Transcendent Story that can touch both broad audiences and tough critics.

Here I introduce the very special sort of story that can reunite the disparate Hollywood and Indie audiences and achieve the filmmaking Holy Grail: critical and commercial success.

Sick of soul-less Hollywood blockbusters? Me too. But I’ve also had a gutful of two-act, too-cool-for-school indie pics. I’m proposing a crazy idea – a rapprochement between Character and Story. No, really, I think it can work.

Here I illustrate the Hero’s Emotional Journey with examples from my own torturous but ultimately rewarding life as a screenwriter.

In my last post, I revealed where I diverge from Vogler on Character Arc. Here I outline a new Hero’s Journey that focuses on the protagonist’s emotional journey.

The ending of Juno’s screenplay is much more powerful the film – and it holds a valuable dramatic lesson for screenwriters.

The Hero’s Journey transformed my storytelling but I fundamentally disagree with Chris Vogler on character arc.

Here I unveil a very special type of subplot – one that can help you deliver an emotionally powerful ending.

There’s one critical thing your subplots should do if you want your screenplay to work.

If you liked my earlier article on how to write a logline, here’s a follow-up piece on the most common weaknesses I see.

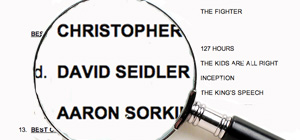

By analysing the categories in which films have (and have not) been nominated, you can tell what worked – and didn’t work – in this year’s crop of screenplays.

The Social Network breaks a bunch of screenwriting “rules” but gets away with it. How?

The Town is an intelligent heist flick but the ending is disappointing – and instructive for students of screenwriting.

How can you make a movie about a guy stuck in a coffin? Here’s how Buried screenwriter Chris Sparling pulled it off and the screenwriting lessons we can all learn from it.

I loved the lead character and adored Emma Stone but the story fails to capitalise on these extraordinary elements.

A lot of screenwriters won’t share their stories until they’re “finished”. Here are 2 reasons you should tell your stories before you write a word of your screenplay.

Christopher Nolan’s Inception is extraordinarily imaginative, brilliantly executed and not even remotely emotionally engaging on any of its 3 levels. Here’s why it leaves me cold.

If all you do at the midpoint is raise the stakes your script has little chance of packing much emotional punch at the climax. Here are the 2 things you should be focussed on delivering around the middle of Act 2.

Over the last 25 years, I’ve stumbled and lurched my way to some understanding of the screenwriter’s craft. Here I share the 10 screenwriting insights I wish I’d had when I started out.

Toy Story 3 reduces men to blubbering wrecks. Here’s why I think it’s so powerful – and it’s not about toy separation anxiety.

The Herald raved about this indie charmer and it is fabulous in parts. But ultimately it didn’t satisfy my own personal definition of a good story.

In LA, they say your film has to take 4 times its budget at the box office to make a profit – but local producer Vincent Sheehan says in Australia the equation is even more daunting.

Local critics are raving and David’s Michod’s crime family drama has some exceptional elements but here I try to balance the hyperbole with a little critique.

Peter Helliar’s debut writing feature is disappointing but buried deep in the film is a high concept that might have made for a huge hit.

There are 4 questions every screenplay should be able to answer. Yet 9 out of 10 scripts don’t. What are the 4 basic questions for dramatic storytelling?

One of the best pieces of advice I’ve ever had about dramatic writing came from Gary Ross. It involves dominoes.

Spielberg won Best Director Oscars for Schindler and Ryan but his Holocaust film won Best Film and Best Screenplay while his other WW2 film won neither. Why?

Beneath Hill 60 is a decent film but it “didn’t connect” with David Stratton. We look at why and how a good basic story could have been tweaked to make a better film.

While the dearly departed Alfred Hitchcock didn’t perform one of his famous cameos in Shawn Levy’s Date Night, the master’s fingerprints were all over the Steve Carell-Tina Fey comedy.

Before you write a single scene of your 120-page screenplay, try to express your film’s logline in 27 words or less. This simple early test can help focus your narrative and save years of wasted effort.

The Hurt Locker, Up in the Air and No Country for Old Men are all good films spoiled by the finales. Have screenwriters forgotten how to satisfy audiences or are they perversely choosing to frustrate us?

One of my students just asked me how his hero could gain courage. This question goes to heart of character arcs so I thought I’d share my response.

There are some fairly obvious story flaws in Baz Luhrmann’s Australia. But the reason it didn’t work was far more fundamental.